As he's done for two decades, Kanaan keeps racing on his terms

NOV 30, 2018

Tony Kanaan knows how he got here. In the general sense.

The specific details of how he, by the end of the 2018 Verizon IndyCar Series season, had made 300 consecutive starts are too numerous to consider. So are the variables. Considering them would be overwhelming, maybe because he’s just a little superstitious at times, and maybe because it would force him to consider the maelstrom he’s driven through all these years, and what was lost along the way.

Because after 21 Indy car seasons and 17 wins – including the 2013 Indianapolis 500 and the consecutive-starts run begun at Portland in June 2001 – Kanaan can be content with the body of work so far for what it is: a testament to virtue in relentlessness. And he’s fine, if not eager, to not discuss streaks until and if he logs another hundred consecutively.

But having stacked so many work days atop each other, in an unforgiving vocation where injury, competition and finance are nefarious co-conspirators, the 43-year-old Brazilian knows how he wants this to end. Simply, on his own terms. Probably, maybe, with AJ Foyt Racing as he has two years remaining on a contract he signed with the promise of helping to return the organization to regular competitiveness.

That’s not to say there’s a timetable. There will eventually just be a realization, Kanaan said. He hopes it’s his.

“That was always my worry even before I made it this far. I think I would love to dictate my own retirement,” Kanaan told IndyCar.com. “In racing, it’s really simple. Either they’re going to fire you or you’re going to say, ‘This is it.’ And I remember watching A.J. I asked A.J. that question, ‘When did you know?’ He said he never planned anything. A.J. said he just woke up one day and said, ‘That’s it.’

“That was always my worry even before I made it this far. I think I would love to dictate my own retirement,” Kanaan told IndyCar.com. “In racing, it’s really simple. Either they’re going to fire you or you’re going to say, ‘This is it.’ And I remember watching A.J. I asked A.J. that question, ‘When did you know?’ He said he never planned anything. A.J. said he just woke up one day and said, ‘That’s it.’

“And I think that’s kind of the way I am. … I think my biggest fear always was someone deciding for me. I’ve always wanted to say when is enough for me, which is very selfish because sometimes A.J. still thinks he can drive an Indy car. So does Mario (Andretti). I don’t want to get to that point.

“You know when it’s that time, but it could be a common decision as well. I think you have to understand the situation you’re in. If I’m getting to that point, I will probably make the decision before anybody else, if I see it’s going to happen.”

Acknowledging all the calamity avoided in making the 300th straight start at Sonoma Raceway in September, and those still ahead when he undertakes the season-opening Firestone Grand Prix of St. Petersburg in March, the 2004 Verizon IndyCar Series champion wants this, clearly thinks he deserves it. And it’s hard to dispute him.

The Raceway at Belle Isle Park in Detroit has been the only culprit in what would otherwise be a perfect career run of more than 360 races. And the bumpy street course took its toll twice, in consecutive years. A practice crash in the 2000 CART event left Kanaan with a broken arm.

“I was out for four races,” he said. “Then I came back and then Detroit, (in) 2001, I crashed in qualifying and I couldn’t race because I had a concussion. Then, (the streak) started. When I came back the next weekend in Portland, it started.

“See? How easy is that to happen. And that’s how you just look back and go, ‘All right.’ I guess for the last 300 times we got fortunate.”

It’s taken more than luck to build the streak

His beard now flecked with disarming grey, but his glint still foreboding when his jaw locks and his eyes widen, Kanaan is still innately too stubborn and faithful to a belief in his powers to think he was less than an active player in getting from there to here. He knows all too well the fragility of the career, how talent must be accompanied by the funding to put it in a car in most cases nowadays.

It’s the new normal. Kanaan has learned that lesson well in his career after Andretti Autosport, when he had to hustle money to fund a ride with KV Racing Technology, with whom he claimed an unlikely and wildly popular win five years ago at “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.”

Kanaan’s eyes widen as if to underscore his next point. Much went into this streak. On the track, and on the phone. But it wasn’t luck.

“I don’t think that’s lucky, having a job,” he said. “You have to be determined and you have to be in the right place at the right time. And you have to perform, I think that’s the secret.

“When people ask how you last this long, unless you have a billionaire parent that will pay for you the rest of your life, you have to hustle, and (a wealthy sponsor) was never the case with me. I refused to give up in 2010 when I left Andretti, and that made me survive this long.”

Many veteran drivers, particularly those who raced before their series implemented stringent concussion protocols, can easily conjure a race weekend when they believe, in hindsight, they were unfit. Kanaan’s comes easily. But he gives every indication he’d do it again.

Many veteran drivers, particularly those who raced before their series implemented stringent concussion protocols, can easily conjure a race weekend when they believe, in hindsight, they were unfit. Kanaan’s comes easily. But he gives every indication he’d do it again.

“Indy 2003, I had a broken wrist,” Kanaan recalled. “I broke it in Japan two weeks before opening day with (Scott) Dixon and I. We had an accident (at Twin Ring Motegi). He was passing me for the lead and we crashed. So, I had broken my wrist and the suspension came inside my leg, which I couldn’t really move my leg for a long time.”

The crash in Motegi is likely remembered as much for what it led to than anything. With Kanaan still recuperating 10 days later and unable to participate in a planned pre-May test at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Mario Andretti – nine years into retirement – eagerly accepted the offer to drive Kanaan’s Andretti Green Racing car. Near the end of the day, Andretti ran over debris that sent the car airborne and somersaulting before miraculously landing upright on its tires on track. The 1969 Indy 500 winner walked away with only scratches.

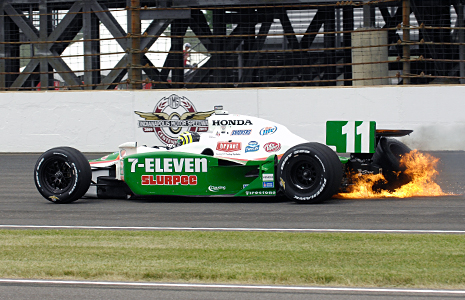

Kanaan recovered in time to qualify second and finish third at Indy that year. But it was six years later at the Brickyard that he endured another crash that could’ve sidelined him.

“In ’09, I had a huge crash in Indy (shown above). My suspension broke and I broke four ribs and I had to race Milwaukee the next weekend and I did it,” he said. “I think (being able to race at) Milwaukee, it was the bigger deal, because a broken hand in a cast, when you go to the 500, it’s the Indy 500, so you can erase any pain. But after having a big crash at the 500 (in ’09), after you’ve just lost the biggest race of the year, it was just a determination to be in Milwaukee, but I don’t regret it.”

Fulfilling a promise and deciding when it's time to say when

Kanaan has made enough money in his career to live well and provide well for his burgeoning family of four children and wife Lauren. He drives sports cars and races expensive bikes in the triathlons he’s taken on as a fitness regimen and competitive outlet. But there is the sense that despite the South Florida and Indianapolis homes and trappings of a lifestyle well above middle-class, Kanaan, mentally if not emotionally, is not far from the concrete floor of a Formula 3 race shop in Italy where he slept as an aspiring racer.

“I’m surprised he’s not more sore than he appears to be, honestly,” said 2016 Indianapolis 500 winner Alexander Rossi, who by comparison made his 50th consecutive INDYCAR start at Sonoma this year. “The schedule is pretty rough, especially when we have the three-in-a-rows like we sometimes do. It’s a testament to the effort he puts in off the track. It’s a very physical six months, and the fact he’s been able to do it for so long and no doubt with some big hits and kind of push through and not miss any races is incredible.”

Father-son analogs are too simple of a plot device in most tales, with the hurt, the motivation, applicable to many men, no matter their level of success. But in the memory of his father, Antoine, who died from cancer when Kanaan was 13, there is the germ of how a middle-aged man who happens to be a race car driver still derives the motivation to persist. Antoine implored his son to take care of his family and not to stop racing. It was a fanciful promise from a boy at the time, but a mantra that seems to have embedded itself onto his being as a man.

“My dad had cancer for three and a half, four years. I remember the first time he went to the doctor, the doctor told him he was going to live three months, and his answer to the doctor was, ‘That’s what you say,’” Kanaan recalled. “And I remember that every three months to the dot, he would send his doctor a note: ‘You’re wrong.’ I guess it was something to keep him going. I think that was a reference for me.

“I have never done another job than racing, so I have to assume that anything I do in my life … I don’t give up. I actually perform better when things are more disturbed. Nothing was ever really easy in my life, so when something is really easy, I get really worried. I’m like, ‘This is too good, man. This is not real. What is going on?’

“I think it made me strong. I won’t listen to anybody and I won’t give up and I think that made me stronger. You get to this point and you’re not having a good year, and everybody has an opinion about what you should do. I’ve been facing that since I was 13 when my dad passed. ‘Oh, you should go to work. This is crazy. You’re never going to make it now.’ But I made it. I don’t listen to anybody. As long as I’m happy and the people I care about are happy …”

Kanaan has lost friends along this journey, countryman and mentor Ayrton Senna in 1994, teammate and comrade Dan Wheldon in 2011 among them. He doesn’t think of himself as a survivor or why it was them, not him, but their deaths seem to stoke him to honor their passing with effort. Until he, unlike them, can decide when it’s time.

“I’m very emotional at times, so I don’t think I would sustain a (farewell) season when people want to do things like they did for (NASCAR star) Jeff Gordon,” Kanaan said. “I wouldn’t make a race. I’d cry all weekend long. I would be emotional. I would be sad that people are going to come see me.

“In a way, I think whenever I decide what that day is, I might just say, ‘Today is the last one. See you later.’”

Until then, no more talk of it.