Race Control serves as nerve center for Indy 500 and all INDYCAR races

MAY 26, 2018

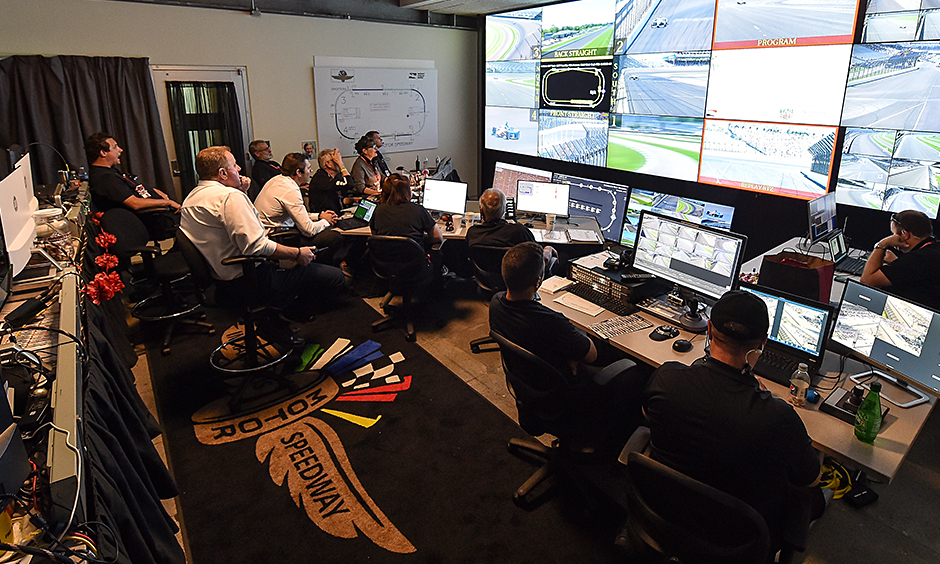

INDIANAPOLIS – In the middle of the second floor of the nine-story Pagoda that towers over the start/finish line at Indianapolis Motor Speedway is a small, windowless room with limited lighting and maximum monitors.

Fifteen big-screen TVs fill the east wall of the room, each showing a different camera angle of the 560-acre IMS grounds. Some screens are divided into nine sections, devoted to stationary cameras around the track. Some screens follow the overall activity on track, others focus on individual portions of it. Some are data only, including a large map of the track showing the location of each car as it moves.

In front of the screens sit a dozen officials, each with a computer monitor and radio headset, eyes fixed on the never-ending stream of information in front of them. More live video feeds are seen here than in the TV trucks parked in infield. At one point during a practice session, two geese wander beyond the fence onto the infield grass on the backstretch. They are immediately seen on one of the monitors. A caution flag is called, and the birds are shooed away.

Welcome to Race Control, the beating heart of the 102nd Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil and the Verizon IndyCar Series. Safety, operations and enforcement emanate from this small space and its dozens of TVs, computer monitors and radios. On Sunday, the small, dimly lit room will be alive with activity. On a typical practice day before the race, though, the mood is attentive but leisurely.

INDYCAR Race Director Kyle Novak is trying to resolve a minor issue with a malfunctioning radar that’s misreading drivers’ speeds as they enter the pits. “It’s happened about 88 times today, which sounds more impressive than the three times it actually happened,” he jokes.

This is where virtually every decision regarding the race will be made. Desks facing the bank of monitors are arranged in an inverted “V,” with Novak at the point, communications director Jim Swintal to his immediate left, chief observer JoAnne Jensen to Swintal’s left and safety dispatcher Jim Norman next to Jensen. Their attention rarely leaves the TV screens and computer monitors in front of them. Everything on track is under their observation.

“There is no way any one person could possibly get to every single one of those views,” Novak says. “You’re talking about 33 cars for 200 laps and how many times those cars are interacting with each other – not to mention pit stops and the interaction on pit lane and equipment and so forth. There’s no way one person could possibly keep an eye on that and evaluate it in the proper time frame.”

Officiating the race is only a small fraction of what faces Novak and his team. Former racers Arie Luyendyk and Max Papis, as race stewards, handle the evaluation of infractions and the enforcement of penalties. The bulk of Race Control’s responsibilities lie in operations – cautions, deployment of safety crews, cleanup, realigning the field and restarting the race.

“The ball-and-strike aspect is just one small part of it,” Novak explains. “Arie and Max make a lot of those ball-and-strike calls with the benefit of our exotic and advanced replay system. But in running the race – where safety is located, what we are going to do in certain situations – there are an infinite amount of situations that can present themselves, and the most important aspect of that is safety. That’s the primary concern of running the race.”

Novak is at the center of a seven-spoked wheel, with all elements reporting to him. They are:

- Instant messaging, which contacts and responds to teams in the pits via instant messages.

- Data, which monitors and compiles statistical input and order of running.

- Red hat, which coordinates the flow of the race with the televising network.

- Safety dispatch, which coordinates with the various fire/rescue teams positioned around the track.

- Communications, which relays pertinent information via radio to teams, drivers and the pace car.

- Track observer, who oversees a team of observers stationed around the track, with particular attention to incidents requiring a caution flag.

- Race stewards (Papis and Luyendyk), who review possible infractions and determine whether an infraction occurred and, if so, apply the appropriate penalty according to the rulebook.

“When I went up to Race Control for the first time – it was Kentucky (Speedway) in 2011 – I just stood there and watched it all happen,” said Luyendyk, who won the Indy 500 in 1990 and 1997. “I was blown away. I never realized what happened there, how involved it is. I’m convinced that not one driver currently driving realizes what’s involved. Once you realize what’s involved and know what’s involved, then you appreciate Race Control more and appreciate stewards more and appreciate the whole thing more.”

Indeed. When the system is working well, nobody notices it.

“Race Control is like mission control for a rocket,” Papis said. “It takes a lot of people behind the scenes in order to make sure that nobody notices anything. When we run a session that is super smooth and nothing happens, that takes a lot of people and effort in order to make sure it happens. It’s complicated and technical. That’s the part of Race Control that impresses me the most. When we do our jobs and everything goes according to plan, people in pit lane think we have done nothing, but that’s actually when most things happen. Just to be able to run a session flawlessly, there are hundreds of calls in order to make that seem seamless. That’s the part that is most fascinating to me. These people are silent heroes.”

>Race Director Novak presides from eye of hurricane

Novak is new to the Verizon IndyCar Series, but he’s not new to directing races. He came to the series from the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, replacing Brian Barnhart when he took a position as Harding Racing’s president.

“My first time as race director, I had the misconception that I had to know everything and do everything,” Novak recalled. “I had to make every last decision and be in control of every last detail, whether it be safety, data review, incident review or talking to the teams over instant messaging or the radio. As a young race director, that was a very overwhelming thought. When I got into the room, I realized that these were some of the most capable people I’d ever encountered in any walk of life.”

The interest in racing began with an interest in cars. Novak and his dad were self-proclaimed gearheads who raced drag cars near their home in Michigan. In his early 20s, Novak became operations manager for a group promoting Champ Car World Series races in Cleveland, Denver and Houston. During that time, he earned a law degree, then became program manager for several sports car support series, then served as race steward for IMSA’s top series before taking over the Verizon IndyCar Series position during the offseason.

The interest in racing began with an interest in cars. Novak and his dad were self-proclaimed gearheads who raced drag cars near their home in Michigan. In his early 20s, Novak became operations manager for a group promoting Champ Car World Series races in Cleveland, Denver and Houston. During that time, he earned a law degree, then became program manager for several sports car support series, then served as race steward for IMSA’s top series before taking over the Verizon IndyCar Series position during the offseason.

It is an all-encompassing, seemingly endless task.

“In contrast to other sports like football, baseball and soccer, every racetrack presents Its own set of challenges,” Novak said. “In football, the field is always 100 yards long and 53 yards wide. Racetracks have differing boundaries, differing runoff areas, differing pit lane entry and exit. They all present their fair share of challenges. We have to adopt a consistent model from racetrack to racetrack that fits in with INDYCAR regulations, that fits in with our culture of officiating and also be able to convey that to the competitors so they can understand it. That’s the bigger picture, rather than just making a call or not making a call. It’s about what goes in to constructing the methodology that goes into the call itself.”

After each race, Novak critiques his team in written form, constantly looking for improvements.

“I have a three-page debrief of each race, and most of those things aren’t pats on the back,” he said. “They’re very situationally detailed. They’re not macro issues; they’re micro issues. … We’re always looking to refine things with the racetrack, with our response, with our communications with the teams to make sure we’re running the best possible competition for fans especially and as well our competitors.”

He also is the point for criticism from teams, drivers, fans and media. Even though individual decisions about infractions and penalties are the responsibility of Papis and Luyendyk, Novak is the one who gets the blame. He heard it after a decision in Long Beach last month to penalize Sebastien Bourdais for an astonishing pass that took him beyond a pit exit line. He heard it again after his decision to restart in the rain at Barber Motorsports Park resulted in a spin by Will Power.

“Yes, you take a lot of heat, you take a lot of pressure,” Novak said. “But when you really look at it from the competitors’ side, it’s their job to win races. It’s their job to gain every position they can. It’s their job to gain every advantage they can. In a series like ours, it’s very close racing. Everyone has the same chassis. The engines are designed to perform well very close to one another. It shrinks the margin of error on that part, but raises the bar in terms of their competitiveness. Everything matters. It’s a competitive business by nature. As officials, we enjoy that competition. We wouldn’t be here if we couldn’t take that pressure cooker.”

When the heat cools, though, Novak feels as if racers and Race Control understand that they’re rowing in the same direction.

“On the back end, you get to know all of these people, and they’re really great people,” Novak said. “They want this sport to thrive despite some of their gripes with calls or asking why we did this and not that. Ultimately, when some of that adrenaline wears off, they are all acting in the best interest of our sport, which makes it that much more special.”

>Race stewards prefer to advise, not penalize

Race Control is more about what people don’t notice than what they do. And people do notice penalties. Angry drivers and owners are bound to be heard from after the race when Luyendyk and Papis make a difficult call. Criticism comes with the territory.

“It’s part of the job,” Luyendyk said. “Most of the time, we get it right. Sometimes we don’t. That’s part of the game. Sometimes we have to make a decision and I’m like, ‘If we only had more time.’ Like when a guy has to give up a position. … In Formula One, they have a different system. They give their guys 10-second penalties, and they literally take a half-hour to come to a conclusion. You can imagine how much luxury that would be. We don’t have that luxury.”

Identifying infractions and penalizing them falls strictly with the series’ two race stewards. On the rare occasion they disagree, the tie is broken by Jay Frye, INDYCAR’s president of operations and competition who also looks on from Race Control. Now in their third season as stewards, Luyendyk and Papis take a hands-on approach to their jobs, talking to drivers before each race, making clear the quirks and ground rules of each track.

Identifying infractions and penalizing them falls strictly with the series’ two race stewards. On the rare occasion they disagree, the tie is broken by Jay Frye, INDYCAR’s president of operations and competition who also looks on from Race Control. Now in their third season as stewards, Luyendyk and Papis take a hands-on approach to their jobs, talking to drivers before each race, making clear the quirks and ground rules of each track.

“You can look at our jobs in two completely different ways,” Papis said. “You can look at it like if you are a policeman, or you can look at it like you are an adviser. I know that I look at my position as an adviser. Obviously, there are rules that are implemented, and we do that, and we do it very fairly. But at the same time, I feel like our presence is really about helping to mitigate the distance between the sport and the competitor. We go to the garages as a preemptive measure, explaining certain situations to drivers. I feel that’s the biggest part of our contribution to the sport – making the best judgment calls we can.”

Reality is, the stewards are just a fraction of the entire Race Control operation. They’re called upon only in specific situations. They’re the umpires, with duties separate from Novak’s, safety, communications and all other functions of Race Control.

“Often enough, I feel a bit insignificant in that way,” Luyendyk said. “I realize that my role is small and there’s so much more to the bigger picture.

“The problem is that we all like these guys. We like the drivers, and we feel for them when they get a penalty. It basically screws up their whole weekend. We hate doing it, but if it’s black or white, that’s the way it is. On the other hand, we try to be proactive. We go to the drivers before the race and say, ‘Hey, if you cross this white line, it’s going to be a drive-through. Just don’t cross it. I don’t want to see you after the race.’ We’ve gotten a lot of good feedback from that. We try to give them a heads-up on certain things. Not all of them really listen, but we try.”

It’s about perception, they say, and one of the aspects that’s in their favor is their racing experience. Luyendyk has 20 years of Indy car experience and 18 Indy 500s to his credit. Papis has decades of experience in Indy car, NASCAR, F1 and sports cars.

“I feel like our competitors see Race Control and myself and Arie and Jay not like enemies, but like resources,” Papis said. “Sometimes we have to make the hard call, and that’s OK. But they know that they did it; we didn’t. There are rules, and they know that.”

If they do have one thing in common, it’s prerace nerves.

“When we get ready for a race, we get the same kind of butterflies we did as a driver,” Luyendyk said.